Current research methods rely on large pools of samples in order to test their hypothesis. For example, population level studies require large collections of sample material in order to investigate the occurrence of a disease or frequency of gene mutations within a disease. New therapies and drugs also need to be tested in a large number of human tissue samples. What all of these research goals have in common is the need for human samples to test. These samples are essential for scientific research, and currently the demand for human biological material is high. Biobanks, which are large collections of human samples, offer a solution.

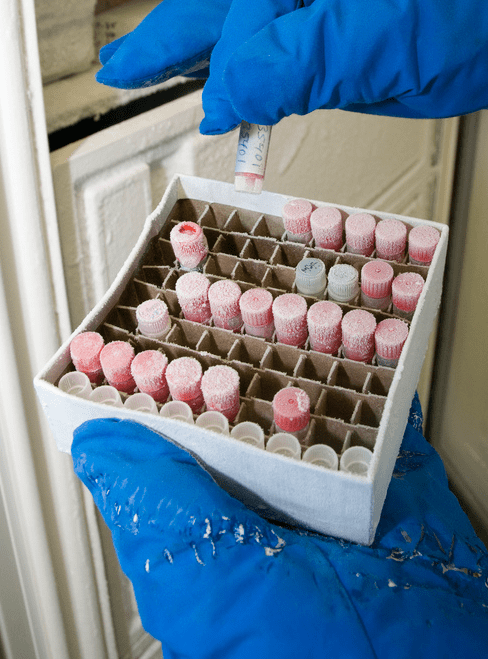

Before the existence of biobanks, each research project collected its own samples. Depending on the project, this could be a very difficult task. Specific research goals demand specific and often rare samples, which are hard to obtain. Project specific sampling also resulted in many separate collections of diverse biological specimens spread out over various research centers. Biobanks were created as a way to organize and consolidate these samples, to accommodate the ever-increasing demand for human samples and to make these repositories of tissue accessible to researchers. Biobanks can essentially be seen as large sample libraries, containing various types of biological samples such as blood, tumor biopsies, DNA fragments, urine, saliva and so on. Scientists can request access to a set of samples to use in their studies.

“Biobanking supports many medical novelties,” says Annelies Debucquoy. “If no samples and associated clinical data are available, it becomes very difficult to evaluate new therapies or develop new biomarkers. It is mainly with samples accessible from biobanks that these technologies can be improved.”

Debucquoy assists in the development of the European biobanking effort, BBMRI-ERIC, and works for the Belgian national node in this European biobanking network. She thoroughly believes that biobanks are a valuable asset in medical innovation. “Before biobanking, each research facility collected samples for its own use. However, they employed various sampling techniques and storage methods. This made the sample quality rather heterogeneous between different institutes, causing further analyses to be unreliable. Biobanks implement certain standards, which guarantee a high quality of each sample in the collection,” explains Debucquoy.

From the operating theatre to the biobank

Samples must be added to the biobanks before they can be accessed for research purposes. So how does this happen? Who contributes to the biobanks? Where do these precious samples come from? Debucquoy answers: “In most cases, biobank samples are taken from hospitalized patients. A distinction is made depending on the purpose of the sample. Some specimens are collected with a specific goal in mind, for a specific study. These are called samples for primary use. Each patient needs to give his or her explicit informed consent, and knows which project their samples will be used in.”

‘Presumed consent’ is something other European countries are jealous of.

“Secondary use samples are taken, in many cases, from a patient for diagnosis or therapy. The unused tissue, which would otherwise be destroyed, is stored in a biobank and can be made accessible for further scientific research. Importantly, at the time of collection of these tissues, it is generally unknown for what research these samples will be used. In addition, secondary use samples have a system of ‘presumed consent’ in Belgium. This means that all of the tissue leftover from routine clinical practice can be used for scientific research, after approval of the project by an Ethical Commission, unless the patient objects. Upon hospital admission, the patient receives a brochure, which informs him or her of this system. ‘Presumed consent’ is something other European countries are jealous of, because it allows for easy collection of many samples and rapid expansion of biobanks.”

Belgium is part of the game

Currently, there are three biobank networks in Belgium. The Center for Medical Innovation (CMI) represents the Flemish biobanking initiative; the Biothèque de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles (BWB) is the Walloon biobanking effort. Lastly, the Belgian Virtual Tumorbank is focusing on the collection of data from human tumor samples and is a federal initiative. Together, this network connects 13 biobanks that are linked to public institutions such as hospitals, universities and research centers. All of these biobanking organizations are represented at the European level by the Belgian national node (BBMRI.be) in the European BBMRI-ERIC. Although the European biobanking network is still in its infancy, it is quickly becoming one of the largest health research infrastructures in Europe.

“Right now, we are working on two aspects of the BBMRI,” explains Debucquoy. “First, the IT infrastructure is being developed and expanded. We have already launched the BBMRI-ERIC directory. This is an online tool that allows anyone to browse through the content of all of the connected biobanks and identify where their samples of interest might be available. This is the first comprehensive overview of European biobanking. At the same time, a lot of work is being put into researching the ethical and legal regulations of biobanking. Our goal is to increase the visibility of biobanks and provide access to large amounts of high quality human samples to scientists all over Europe.”