The pollution arising from plastic refuse at sea is not only a question of the plastic itself but also of the bacteria and chemicals that cover the plastic, according to researchers from the Institute for Agriculture and Fisheries Research (ILVO) in Ostend, Belgium. On samples of plastic waste, ILVO has found over 250 kinds of chemicals and a specific community of bacteria, some of which can cause disease. Animals such as shrimp and sprat swallow microscopic pieces of plastic and are thus exposed to toxic substances and bacteria. The entry of these chemicals and the resulting diseases could effect the entire marine food chain.

The effects of this are still under study but ILVO is not wasting any time to find ways to reduce the amount of plastic waste in the sea. One solution is to find biodegradable alternatives for the plastic in fishing nets; another is to search for bacteria that can break down the plastic itself and the chemical coating in seawater. Using advanced DNA-based techniques, a gigantic number of bacteria can be screened for characteristics that help the bacteria break down plastics or chemicals. Scientists are thus convinced that soon they will be able to start performing tests on organic breakdown of plastics in the sea.

Problem of plastic waste

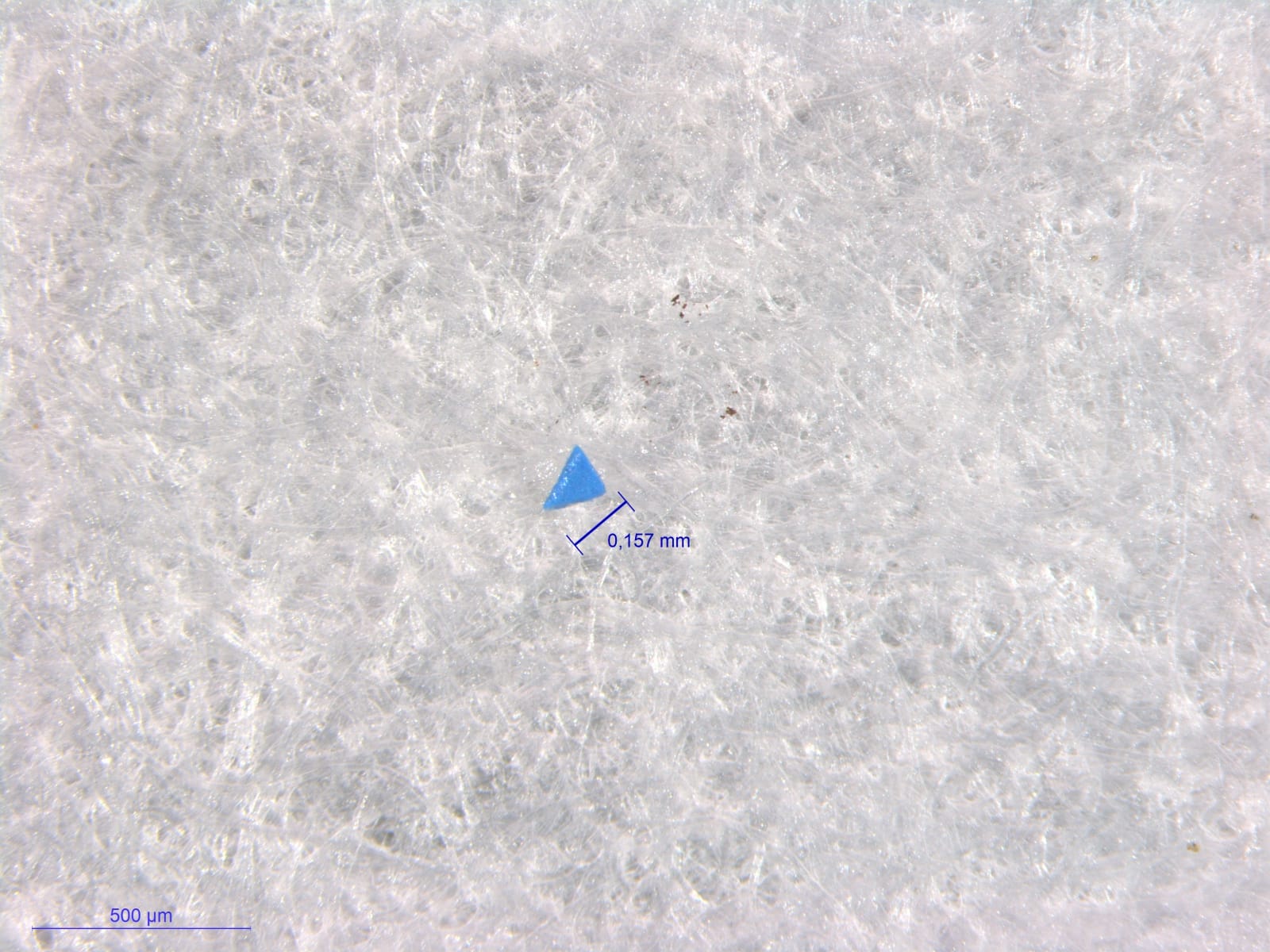

Every year, an estimated 20,000 tonnes of plastic waste ends up in the North Sea alone and comes from the shipping industry, fisheries, tourism and rivers. A majority of the plastic is large or medium-sized pieces that float on the surface, are washed ashore, sink to the bottom, or break down into smaller pieces. Another important source of plastic waste is the wastewater from washing machines (often originating from fleece textiles), cosmetic products such as facial scrubs, and industry, which produce microscopically small particles. These “microplastics” are a threat to the marine environment as they appear to be magnets for chemical substances and bacteria.

Impact on sea life

Scientists from the ILVO have identified more than 250 different chemicals on plastic waste and microplastics in the ocean. In addition they identified that plastic waste harbors a specific community of bacteria that is different than those found in seawater or on the seafloor. Some of these bacteria, such as certain types of Escherichia coli, Vibrio and Pseudomonas, can potentially cause disease. Research has shown that 63% of the shrimp and 39% of the sprat caught in the North Sea have ingested microplastics. On average, only 1 piece of microplastic was found per individual but the animal quickly excretes the microplastics.

During the digestive process the animal is exposed to toxic chemicals and disease causing bacteria coating the microplastics, whether the chemicals are released depends on the strength of their bond with the plastic. Tests with PCBs (which are very resistant to decomposition) have shown that the PCBs do separate from the microplastic during digestion. Therefore the toxins and bacteria are able to be released from the surface of the plastic and taken up by the sea-dwelling animals and enter into the food chain.

Lisa Devriese, ILVO researcher: “Although the effects of microplastics, including their ‘jacket’ of chemicals and bacteria, are still being intensively studied at ILVO and other research institutions worldwide, ILVO is already developing several strategies to address this problem.”

Solution: to use biodegradable materials

The first strategy is one of prevention. ILVO, together with the fisheries industry and Dutch partners, is looking for a degradable alternative for the plastic “dolly” ropes that are attached to protect commercial beam trawl fishing nets to protect them from wearing out. As the beam trawl is dragged along the ocean floor, the dolly ropes start to fray and fragment, thus a large portion of this synthetic polyethylene is released into the sea. An estimated 90 to 130 tonnes of dolly rope are bought every year by the Belgian fishing community. Nearly half of this ends up in the sea, contributing to the plastic waste problem.

But there is good news: “From interviews with fishermen and suppliers, it appears that the fisheries industry is willing to consider using biodegradable materials, on the condition that they are more sustainable, cheaper and equally effective against net damage as the plastic equivalent,” said Karen Bekaert, ILVO researcher. Natural materials such as hemp, flax or sisal can be used into combination with another material such as bioplastics. Also animal-based products such as keratin, which can be found in chicken feathers, are already being used in practical applications and could serve as an alternative for polyethylene dolly ropes. Other alternatives include degradable synthetics such as polylactic acid (PLA), polybutylenesuccinate (PBS) or cellulose and starch-based plastics. All of these alternatives are already being tested aboard research vessels for their strength and effectiveness against net damage. Ultimately, the use of such an alternative could eliminate the thousands of kilos of polyethylene that end up in the sea each year.

Solution: using bacteria to degrade plastics

ILVO researcher Caroline De Tender: “Using advanced DNA-based methods, we screen the genetic characteristics of the species living on the plastic to look for characteristics that allow the bacteria to either break down the plastic itself or to break down the chemicals that attach to, or are embedded in, the plastic waste.” Research on the bacteria living in the ocean is still in the early stages, but on land a number of bacteria have been discovered that can break down plastics and chemicals. The researchers are hope that within the coming years, similar testing will be done using sea-dwelling bacteria to break down plastic waste in the ocean.