Lifesaving therapies

Gene therapy has been on the market since 2012, albeit with little commercial success so far. This is likely to change now that two novel drugs with blockbuster potential have entered the scene.

Zolgensma is a life-changing gene therapy aimed at treating infants with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), a disease caused by bi-allelic mutations in the SMN1 gene. Zolgensma has the potential to expand the lifespan of these patients from less than 2 years to well into adult age. Novartis launched the product in May 2019 in the USA at a price of $2.1 million.

The other drug, Zynteglo, will initially be launched in 2020 in Europe by Bluebird at an estimated cost of about €1.6 million. Zynteglo is aimed at a subgroup of patients with transfusion-dependent ß-thalassemia (TDT), due to a mutation in the beta-globin gene. This makes them dependent on lifelong chronic blood transfusions for survival, at the risk of progressive multi-organ damage due to iron overload. Zynteglo adds a modified beta-globin gene into the patient’s own hematopoietic stem cells, enabling production of hemoglobin in the body at sufficient levels to allow independence from constant blood transfusions.

Is the treatment worth the price?

Although these product’s prices look outlandish at first sight, they have been relatively well-received by the health community. To understand why, we need to remind ourselves that gene therapies have the potential to provide a lifelong cure with a single treatment. So, the price needs to be spread over the number of years that the patient benefits from the treatment.

For the treatment of SMA, there is only one other approved drug: Spinraza, an antisense-oligonucleotide from Biogen. Spinraza has to be continually administered via three intrathecal injections per year, costing $750,000 for the first year, and $375,000 for each subsequent year. If Zolgensma is effective over a ten-year period, the cost per year would be $210,000. This is still a significant amount, but within the ‘normal’ range for disease-modifying treatments of rare diseases.

Comparisons aside, is this high price justified by the value the treatment brings to the patient? In Europe, this question is typically addressed by governmental Health Technology Assessment (HTA) agencies like NICE in the UK or IQWiG in Germany. In the USA, the HTA role is mainly filled by ICER, which is an independent non-governmental organisation that wields increasingly strong influence on decisions of health insurance payers.

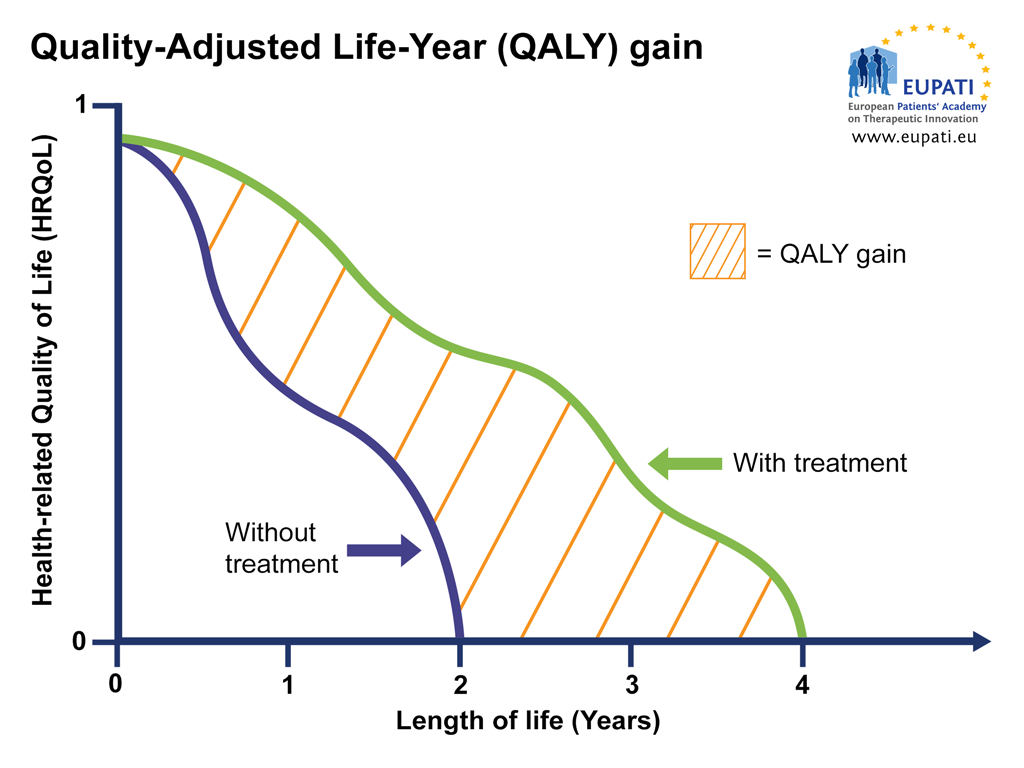

HTAs are continuously refining health economics models to establish the cost-benefit ratio of drugs based on objective criteria. At the centre of these models is the concept of QALY (Quality-Adjusted Life-Year), which attempts to capture the impact of a treatment on both the patient’s length of life and health-related quality of life.

Image: QALY attempts to represent the impact a therapy has on the length of life while also taking into account any changes in the health-related quality of life (HRQoL). HRQoL is calculated on a scale where 0 = ‘death’ and 1 = ‘perfect’ health. This means that, for example, 4 years at perfect health is 4 x 1 = 4 QALY, but 4 years at sub-par health is 4 x 0.5 = 2 QALY (image courtesy of EUPATI).

ICER’s standard model for assessing cost effectiveness of a treatment uses a threshold of $150,000 per QALY, and $500,000 for ultra-rare diseases. Using these metrics, ICER established that Zolgensma is cost effective at the $500,000/QALY threshold, even if it would be priced at $5 million, well above the actual $2.1 price mark. For Zynteglo, NICE’s assessment report is expected by mid 2020.

Meanwhile, Bluebird has performed its own health economics study and insists that the anticipated €1.6 million price tag is below the cost-effectiveness standard $150,000 per QALY cost-effectivity threshold, even without factoring in offsets in supportive care costs for the patient. This is in marked contrast with many of the newly launched conventional drugs treating orphan diseases. According to ICER, for instance, the small molecule drugs Symdeko and Kalydeco, both cystic fibrosis treatments from Vertex, would have to be sold at half their price in order to reach the $500,000 per QALY threshold.

An innovative pricing model

One differentiating feature of gene therapy is that the treatment is typically given once rather than continuously at regular intervals. This brings dilemmas to gene therapy developers: should they charge for the therapy immediately, or in instalments? What happens if the treatment is paid for, but isn’t effective or loses efficacy over time? Should the patient get a free repeat treatment if the therapy wanes before a certain date?

For Zolgensma and Zynteglo, both Novartis and Bluebird have chosen a payment model with annuities over a 5-year period. Additionally, in Bluebird’s payment model for the European launch of Zynteglo, the vast majority of the annuities will be performance-based. In total, 80% of the drug’s cost will be contingent on the patient’s continued response during the first 5 years of the therapy. Although Novartis also claims to be in favour of such model, a maximum 17.1% of Zolgensma’s $2.125 million price in the USA will be performance-based, due to current limitations pertaining to Medicaid’s ‘best price’ rule.

Zolgensma and Zynteglo show that it is possible to introduce an innovative pricing model that is both value and performance-based, even for a therapeutic modality that is more complex than conventional drugs. Novartis and Bluebird have broken away from the old pharma company habit of setting the prices of game-changing drugs at the highest possible level, regardless of value and performance.

Multiple companies will soon be ready to release new gene therapies from their well-filled pipelines. If these companies copy the Zolgensma and Zynteglo models, these performance-based modalities have a good chance of becoming firmly rooted over the next decade.